For some patients, SARS-CoV-2 doesn’t just run its course. They continue to experience myriad sequelae after the acute phase of COVID-19. Long-term symptoms vary. Some, such as cardiopulmonary issues, are serious; some, such as alterations in anosmia and hypogeusia, are less so, but they continue to alarm patients for weeks to months after the original illness. These patients are truly in it for the long haul.

“Once they were discharged from the hospital, patients were so happy that they got over the illness, that they survived,” said Soo Yeon Kim, MD, the medical director of musculoskeletal medicine and an assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation, at Johns Hopkins Medicine, in Baltimore. They expected to return to their normal lives. “They go back to work and then realize that, oh, their executive functions are not as good as what they were before.”

Kim also has seen patients who never were admitted to the hospital with post–COVID-19 sequelae. “The patients who were never hospitalized can present with severe ongoing cognitive, functional and mental issues, which may affect their life significantly,” she added, and they did not expect to have these ongoing symptoms because they were not seriously ill in the first place (Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;27[2]:258-263).

“What we are seeing is prolonged issues with lung function, and with the ability to walk distances or having the ability to just have day-to-day functionality,” said Susan M. Mashni, PharmD, BCPS, the vice president and chief pharmacy officer at Mount Sinai Health System, and an associate professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in New York City. “And, of course, [there’s] the post-COVID brain fog that people talk about, with neurologic difficulties in their inability to concentrate, overwhelming feeling of fatigue, and just the inability to really sit down and keep on a task for a long period.”

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms reported, “sometimes weeks, even months, after apparently recovering from COVID,” said Rajesh T. Gandhi, MD, FIDSA, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and the director of HIV clinical services at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston. “That’s sometimes accompanied by brain ‘fog’ or a cognitive feeling that is ‘off’—that is different than they were before the infection.”

In addition to the abovementioned issues, continued anosmia and hypogeusia, gastrointestinal problems, rashes, arthralgia, and alopecia are also common occurrences, according to Luis Ostrosky-Zeichner, MD, FIDSA, a professor and the chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases, and the vice chair of Medicine for Healthcare Quality, at the McGovern Medical School, part of UTHealth in Houston.

“It’s almost like the symptoms are a continuation of the symptoms they had when they had COVID,” said Ostrosky-Zeichner, who is also the medical director of epidemiology and antimicrobial stewardship at Memorial Hermann Texas Medical Center, also in Houston.

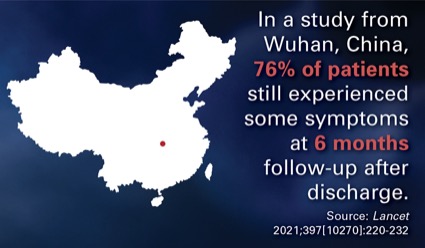

Although most symptoms resolve within weeks or months, some patients still have symptoms a year later, the experts told Infectious Disease Special Edition. In a study from Wuhan, China, 76% of patients still experienced some symptoms at six months follow-up after discharge (Lancet 2021;397[10270]:220-232).

There is no clear consensus definition for post–COVID-19 syndrome, but now that the number of acute cases is slowing, and the hospitalizations and deaths are declining, researchers can turn their attention to finding out more about this manifestation that patients call “long-haul COVID.”

Why?

Although there is a multitude of various symptoms, they fit into various containers: cardiology, neurology, physiatry, psychiatry and psychology, and pulmonary.

One of the things that every health care provider will consider when looking at a patient with long-haul COVID-19 is “who the person was before this started happening to them,” said Kathleen Bell, MD, the Kimberly-Clark Distinguished Chair in Mobility Research and chair of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, in Dallas.

In the case of many long haulers, “we’re seeing a lot of people, for instance, with diabetes, with obesity, with hypertension, who have all of those kinds of preexisting diseases that predispose them to having more severe infections with COVID,” who are also seeing post–COVID-19 syndrome manifest as worsening of their comorbidities.

For instance, those with hypertension might see chronic microvascular disease in the brain. Those with diabetes could see chronic neuropathy in their extremities, she explained at a press briefing sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). The disease itself can cause “all sorts of problems with inflammatory responses in the brain, around the heart, around the muscles, etc.,” she said.

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, which manifests as extreme fatigue, headache, nausea and dizziness, is common, according to Kim, as are myocarditis and exercise intolerance.

In addition, Bell added, issues follow the trauma of an extended ICU stay that can affect the mental health of the person, including depression and anxiety.

“What is not fully understood is if these symptoms are unique to COVID-19, are a general post-viral syndrome that is just being recognized because of the sheer numbers of recovered patients; or are the result of a long ICU stay for those who had severe COVID infection,” noted Allison Navis, MD, an assistant professor in the Division of Neuro-Infectious Diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine, who also spoke at the IDSA briefing.

The long haulers with an extended ICU stay often had prolonged periods of medication-induced coma and delirium, were likely to received continuous neuromuscular blocker therapy, and experienced damage to organs other than the lungs. Patients with a prolonged critical illness like this, regardless of whether COVID-19 is the underlying cause, frequently suffer post–intensive care syndrome (i.e., PICS), explained John W. Devlin, PharmD, a professor of pharmacy at Northeastern University and an associate scientist in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston.

“Patients with PICS may experience prolonged post-ICU cognitive decline, psychologic sequelae including PTSD, depression, anxiety and poor sleep,” which can make it difficult to determine “in those COVID-19 ICU survivors whether the PICS is partially related to persistent effects of COVID-19 or simply related to their prolonged critical illness and PICS-related sequelae of it,” Devlin said.

“During prior ICU COVID-19 surge situations, delivery of the ABCDEF bundle, an interprofessional, multicomponent strategy focused on daily sedation interruption, delirium recognition and reduction, early mobilization, and family engagement—and shown to reduce post-ICU PICS—has been compromised,” Devlin explained.

Never Hospitalized

Although those who had moderate to severe COVID-19 that resulted in an ICU stay are more likely to see a continuation of their COVID-19 symptoms, the really puzzling patients are the ones who were never hospitalized. Many report having brain fog and other cognitive issues, anosmia and hypogeusia, rashes, depression, breathlessness, and difficulty walking, as well as many of the other symptoms suffered by those who had more severe COVID-19.

One study explored 20 athletes with mild to asymptomatic COVID-19 and found imaging evidence of myocarditis in five. The damage was enough to restrict their participation in professional sports (JAMA Cardiol 2021 Mar 4. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0565).

“In general terms, my observation is that the more severe that COVID is, the more likely people are going to end up with long-term symptoms,” Ostrosky-Zeichner said, “but occasionally, we do find somebody that had a relatively mild illness, and they have more severe long-term issues, but that is not the rule.”

However, Navis has found that “the vast majority” of her post–COVID-19 patients were not hospitalized.

Bell agreed that her group also has seen persistent symptoms in patients who were never hospitalized, but that doesn’t mean most of those people were not very sick. “There are a number of people who self-treated, self-quarantined at home who still may have been ill for two, three, four or five weeks—acutely ill, but managed at home,” she said.

Gandhi agreed. “Certainly, there are people who have severe disease that then take weeks, if not months, to get better. What’s less clear is whether the severity of the initial COVID predicts the likelihood of long COVID. We don’t know that yet.”

Management

While researchers are still working to better understand the syndrome—the National Institutes of Health recently announced a study to identify the causes of and the treatment for post–COVID-19—providers are focusing on managing the symptoms that are so distressing to patients.

COVID-19 specialty clinics are cropping up all over the country, and many of the experts interviewed by Infectious Disease Special Edition work with these clinics. Harvard, Hopkins, Mount Sinai and UTHealth are among the institutions that developed clinics early last year based on the patients they were seeing, and have become the standards for care.

But not all clinics are created equal, the experts said. Any health care provider wanting to refer patients should take a close look at those providing care, the experts suggested. Because the symptoms are so diverse and very few patients have only one symptom, the workup and management of long haulers takes a multidisciplinary team, Gandhi said, including pulmonologists, neurologists, rehabilitation medicine specialists, etc.

The initial workup includes a thorough physical examination looking for organic explanations for the symptoms, Ostrosky-Zeichner explained. Blood work is typically done to review renal and liver function, among other things, and then other tests are ordered based on the presentation.

“It’s fairly important not to assume that everything is due to COVID,” Gandhi reminded, “and to make sure you have an open mind as to what else might be causing this.”

Bell agreed. “You can never take a presentation of a patient and divorce it from who the person is and what their environment and context is. So, [for] every single person who comes in, whether they have COVID or they don’t have COVID, it is very important to put that person into context of who they were before, what their premorbid conditions were and what the context of their lives are,” she said.

“I like to work up the specific symptoms if it seems appropriate,” Navis added. “So, for example, I will do blood work to look for potential causes that could be contributing. If there are more severe deficits with the neuropathy, for example, I might get nerve conduction studies.”

If someone has vascular risk factors, some imaging might be in order, she added. “I do like to get cognitive testing for everybody.”

Then other tests will depend on the symptoms. For instance, if the concern is headaches and brain fog, MRI might be done to look for inflammation or ischemia. Cardiopulmonary issues might require chest radiographs, CAT scans, an echocardiogram or pulmonary function test. This is one reason why it helps to have a team of specialists available for consultation, they said.

Regardless of the reasons that bring the patient to the office or clinic, there is no cure for post–COVID-19 syndrome, but there are medications that can be prescribed to help alleviate some of the symptoms.

These need careful consideration, according to Navis. For instance, if a person is suffering from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder and can’t sleep, a drug that might be sedating might be considered, but it might not be appropriate for someone who reports depression and fatigue.

This is where a pharmacist could play an important role on the team, ensuring that the medications subscribed by various specialists work together to improve the situation, Mashni said.

Some of the best medicine, Gandhi said, is to listen to patients and understand what they are going through as they try to put their lives back together.

“We need to take this seriously,” he added. “Many millions of people have been infected. Many will resolve on their own, but not all of them will, and we need to help them.”

The sources reported no relevant financial disclosures.