By May, COVID-19–related hospitalizations and deaths were continuing to decline, people were venturing out, and mitigation measures were loosening. Infectious disease and public health specialists, especially in big cities like New York, dared to take a breath after almost three years of battling the pandemic nonstop.

Monkeypox virus (MPV) had other plans.

People can travel to almost anywhere in the world within 24 hours, so it was probably not surprising that monkeypox—a disease that has been around for decades in Africa—was now being seen in countries where it is not endemic. Public health officials admitted they were stretched thin by the time the 2022 outbreak began, however. After COVID-19, hepatitis of unknown origin in children and various other smaller outbreaks, one public health official wryly described 2022 as “the gift that keeps on giving” after MPV arrived.

The COVID-19 response caused a “fair amount of burnout,” agreed Kevin L. Ard, MD, MPH, the medical director of the National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center at The Fenway Institute, and the director of the Sexual Health Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston.

“It’s not like COVID was over, and people recovered. This [MPV] was really grafted on top of that,” Dr. Ard said.

In addition, there were all the other issues that public health officials manage, such as smoking cessation, cardiovascular disease and immunizations. Many of these programs were put on hold during the pandemic, and public health officials were just starting to put them back on the public’s radar, added Noreen A. Hynes, MD, MPH, the director of the Geographic Medicine Center of the Division of Infectious Diseases at John Hopkins, in Baltimore.

The MPV epidemic cannot be compared in scope to the COVID-19 pandemic, of course; COVID’s effect on the world was far more disruptive and devastating. The reproductive number for COVID-19 was about 2.4 and that for MPV was only 1.29 (J Travel Med 2022 Aug 5. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taac099). Still, how quickly MPV spread to the 106 non-endemic countries and territories, its mode of transmission and its unusual presentation during this outbreak were concerning.

“We’ve had the occasional outbreak from imported exotic animals or the occasional traveler, but nothing like this,” Dr. Hynes said. “Monkeypox is not acting right now the way we thought monkeypox should be acting.”

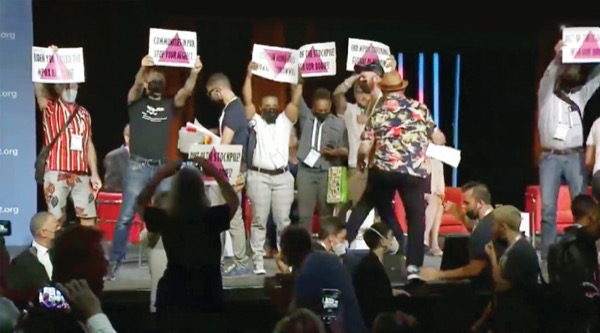

Many of the lessons learned from battling COVID-19 were applied to the MPV response, and although it might not have been fast enough for those affected—protesters took the stage at one of the AIDS 2022 sessions to protest the lack of MPV vaccination in July—the outbreak was controlled fairly quickly and appeared to be trending downward in September.

Getting Up to Speed

Cases began appearing in several countries, including the United States, mainly among men who have sex with men (MSM) after several large gatherings in May, including Maspalomas in the Canary Islands and the annual Darklands Antwerp Fetish Festival in Belgium. Reminiscent of the bathhouses in San Francisco at the beginning of the HIV epidemic, Madrid saunas were also linked to the outbreak.

The occasional MPV case that resulted from travel is not new, but this was the “first time that many monkeypox cases and clusters have been reported concurrently in non-endemic and endemic countries in widely disparate geographic areas,” explained the World Health Organization (WHO), which declared MPV a public health emergency of international concern in July.

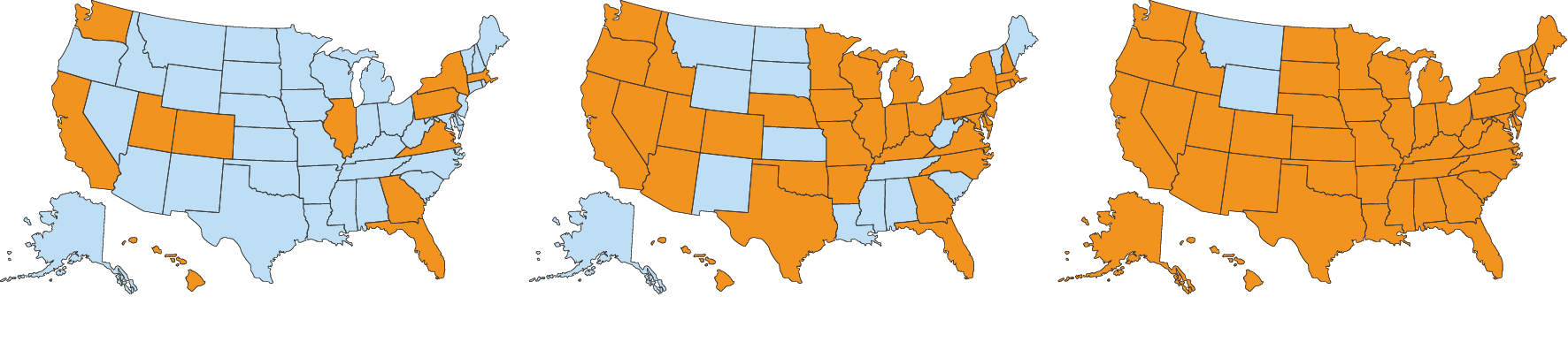

At one point in the summer, the United States was seeing almost 1,000 cases per day, but by Sept. 24, daily cases were below 200. At this writing, the United States confirmed 25,509 cases in all 50 states, Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C. One U.S. death from MPV had been reported by Sept. 29. The WHO reported 67,556 laboratory-confirmed cases and 27 deaths in 106 countries across all six regions of the world by Sept. 29.

“This infection got into a certain social and sexual network, and that allowed it to spread in a wider fashion than before,” Dr. Ard said.

In addition to these large international parties, there could have been low levels of circulating virus not detected by surveillance systems. In that case, sustained human-to-human transmission could have gone undetected for some time, according to Mary Foote, MD, MPH, a medical director at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

“We have evidence to show by looking at the sequencing that this outbreak virus is closely related to a previous outbreak strain and has probably been circulating in humans for longer than we realized,” Dr. Foote said (Nature Med 2022;28:1569-1572).

“We had these huge events in Europe that were associated with the early outbreak cases, where people from all over the world attended with many engaging in sex with a lot of partners, who then went back to their home countries. Many were engaging in sexual activity once they returned home before the outbreak was even detected,” she added.

“There were quite a few differences actually in what we’re seeing in 2022 compared with our previous experience with monkeypox in an African setting,” noted Matthew M. Hamill, MBChB, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

Sexual transmission is one new characteristic. Although sexual transmission of MPV is atypical, it was reported by a Nigerian doctor in 2018, who said nearly half of the people he treated in one outbreak had genital lesions (Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24[6]:1149-1151).

“If you’d asked me five years ago, what was the main mode of transmission for monkeypox virus, I certainly would not have said sex. We think of it as being something that spreads through close nonsexual household contact, and from people handling linens or towels and other items that may be carrying infected material,” Dr. Hamill said.

“I think it’s the first time that there’s been widespread recognition that the infection could be spread in the context of sex,” said Dr. Ard, who is also an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, in Boston.

The presentations in these cases were far from typical, so that also could have delayed recognition. “People are not having such a reliable prodrome where they have a flu-like illness followed by the rash,” Dr. Hamill said.

Some people are experiencing those flu-like illnesses before the rash, some at the same time as the rash erupts, and others have no prodrome at all—they just break out in a rash, he explained.

And many people who have respiratory illnesses during a COVID-19 pandemic are more likely to be sent for COVID-19 testing than MPV testing, they said.

“One of the things we’ve learned is [sometimes you need] to test outside of the testing criteria,” Dr. Ard said. “You will never find the patients to whom this infection is spreading if you always only test one group.” Although most cases are appearing among MSM, other people can and have become infected, he reminded.

“There is a lot of diagnostic uncertainty at the prodromal stage because of the respiratory symptoms. It could be someone with COVID. They could have influenza or a strep throat brewing,” Dr. Hamill said. “Look for lymphadenopathy, which isn’t a particularly discriminating feature, but is a feature of monkeypox.”

Painful Process

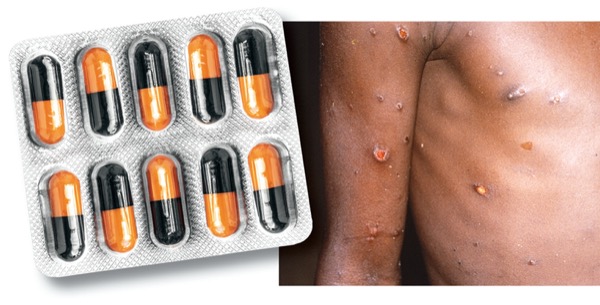

Another difference in presentation is the number of people with a rectal infection that is causing proctitis, which has proved extremely painful, as are the lesions appearing in the mouth, back of the throat, anus, rectum and vaginal areas, all the experts said.

The pain is frequently out of proportion with the clinical findings, they said, and often inhibits bodily functions such as eating and defecating. Managing this pain is one of the reasons patients end up hospitalized, according to Dr. Foote. “Stool softeners to ease bowel movements, topical pain medications [are being used], but sometimes they need more aggressive prescription medications like gabapentin or opioids,” she said.

Topical steroids to control the inflammation have also been used, according to Dr. Hamill.

“We try to address pain as much as we can and that can be with topical treatments or painkillers,” Dr. Ard said. “Another strategy is to use the antiviral TPOXX [tecovirimat (Siga Technologies)].”

Prophylaxis and Treatment

Many questions remain about tecovirimat and Jynneos, a modified vaccinia ankara vacine, by Bavarian Nordic A/S, according to Dr. Hynes, not least of which is whether they work for monkeypox and when they should be used.

“When is it appropriate to use them? Are vaccines most appropriately used before exposures? How many days afterward can they be used? Is TPOXX only good for treatment? Can you use it for prevention pre-exposure or post exposure?”

Tecovirimat is a core treatment for monkeypox, with anecdotal reports that it shortens lesion healing to about three or four days rather than three or four weeks, but everyone is still waiting for data to confirm this. Tecovirimat is approved to treat smallpox, not other orthopoxviruses, Dr. Hynes explained.

So, it is being used under a non-research, expanded-access investigational new drug (EA-IND) protocol (https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/pdf/Tecovirimat-IND-Protocol-CDC-IRB.pdf). The EA-IND can make it difficult to obtain the medication, experts said.

“How easy is it to get? That is a very complicated question,” Dr. Foote said. “It depends on what jurisdiction you are in and what resources your institution has to support the extra work required. The CDC has been very responsive to our feedback about improving and streamlining the IND processes, however.”

Since the medication is only available through the federal Strategic National Stockpile, every health department has had to develop their own processes to distribute the medication. New York City took advantage of the processes set up for COVID-19 and was able to use a central pharmacy with home delivery, so all New Yorkers can have access to the medication, she explained.

The difficulties have lessened, Dr. Ard agreed, but they are still present. The provider has to already be registered with the CDC before it can be prescribed under the EA-IND.

“When we start TPOXX, we need to obtain their informed consent, which is one document, and then there is an intake form we have to fill out for the patient,” Dr. Ard said. “This is in contrast to routine medicine that we would provide during clinical care, where we just write a note and send a prescription to the pharmacy.”

The CDC updated its EA-IND protocol in August, but it is still a 22-page document with several steps (https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/obtaining-tecovirimat.html). “The CDC lessened the paperwork, but there still is more than usual care,” he said. “I think that contributes to it still being more limited than otherwise would be because many clinicians and clinics just aren’t able to overcome those administrative barriers to even start the process.”

Dr. Ard added that in a university or hospital clinic setting, many people are relying on the pharmacists to help. “I think it would be hard for any clinic or clinician to do it without the help of others, like pharmacists. Our pharmacists do help,” he said.

Much of the public health response has centered on vaccination with Jynneos. Although the vaccine has a safer risk profile than ACAM2000, its efficacy in preventing monkeypox has not been studied, according to Dr. Foote.

The initial rollout of the vaccine was reminiscent of the early COVID-19 vaccine rollout, with people having a difficult time accessing the two-dose vaccine. At first, healthcare providers were told to delay the second shot until their supplies increased. The limited distribution of the vaccine prompted the protest at the AIDS 2022 meeting, where one protester said he traveled from New York to the meeting in Montreal to be vaccinated.

In August, the FDA granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) to allow intradermal injection of the MPV vaccine for people ages 18 years and older, which increased the total number of doses by fivefold. Subcutaneous injection would remain for children.

“In many places, the initial vaccine strategy was one of a first-come, first-served approach,” Dr. Ard explained. “And of course, the people who are able to do that are the ones who can take time off from work, who are closely linked to health information, and so you are not necessarily reaching a broad swath of people who may benefit.”

This led to inequitable distribution of the vaccine, and today new MPV cases are occurring more rapidly among Black and Hispanic individuals, according to the CDC.

Contact tracing in this outbreak was particularly challenging, according to Dr. Foote, especially at the beginning of the outbreak when people were first returning from Europe and attending large local events. “There were a lot of anonymous encounters at gatherings and the use of apps so tracking down every high-risk contact was not possible,” she said. “So, we learned very quickly that we had to take a more expansive prevention approach.”

In addition, the nature of the infection—having gotten it from a sexual encounter—also hinders tracing, according to Dr. Hamill.

“There are reasons why [the usual questions required for contact tracing] might not work well in this sort of an epidemiological moment. If somebody acquired monkeypox infection through close contact of a sexual nature with an anonymous partner or a partner they don’t trust, they may be fearful. They may be unwilling to provide the contact information to the health department. These are the same kinds of issues we have with other STIs.”

Because the public health officials could not find all the contacts, they focused on the most likely contacts based on their risk stratification and recommended vaccination for them.

In addition, federal public health officials provided vaccines at large Pride and other LBGTQAI+ events throughout the country.

Although Monday morning quarterbacking is always spot-on, most of the physicians interviewed thought the public health response was fairly good, especially in the way the message was delivered.

“They were very careful from the beginning to not stigmatize any group of people,” Dr. Ard said.

One important lesson learned from COVID-19 is that information has to change as more data become available. “We have become very used to public health guidance shifting with little notice because of COVID,” Dr. Ard said. “That happened with monkeypox as well. In Massachusetts, for example, we began doing a two-dose vaccine strategy. We shifted to a first dose prioritization only. A few days after that, the FDA released the EUA for intradermal dosing, and we shifted back to a two-dose strategy, but not intradermal.”

Helping the response was communicating directly with the communities that were most affected, according to Dr. Foote. Messaging and appropriate guidance were important.

“I think the state and local public health response was actually pretty extraordinary, considering the challenges and some of the limitations we were up against,” Dr. Foote said. “Giving culturally appropriate guidance using a harm-reduction approach is really important and I think a lesson for all of us during every response.”

However, Congress has not released funds for this response and that is “something we would love to see,” Dr. Foote said.

The sources reported no relevant financial disclosures.

{RELATED-HORIZONTAL}