By Marie Rosenthal, MS

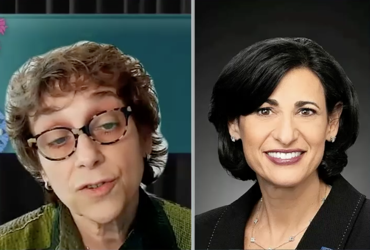

COVID-19 shined a light on several challenges, including a lack of public health infrastructure, but the one that most HIV physicians will recognize immediately is health inequity, Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, told Elaine Abrams, MD, who interviewed the director of the CDC at CROI 2022 on Feb. 13.

“We in the work of HIV have always looked at the importance of health equity in making sure that we serve everybody,” Dr. Walensky said. “We’ve known this in public health. We’ve known this at the CDC, and yet, COVID shined such a white light on issues related to health equity.

“The fact that life-expectancy losses were three years in Hispanic populations; 2.9 years in Black populations associated with COVID,” she said; “combined with the decrease in diabetes care and cancer screening, cardiovascular disease, certainly in HIV and hepatitis C and maternal [healthcare] for many patients underscores the need for healthcare providers to work toward a more equitable health delivery model.

COVID-19 continues to affect underrepresented, vulnerable communities that have increased rates of comorbidities and less access to care, she said. “So, I think that this is one area where we really do need to focus our energy, … one that we needed to work toward and understand, because I think no one will be healthy until everyone is healthy,” Dr. Walensky said.

And that health equity needs to be worldwide, she added, not just a right of people in the United States.

She pointed to the success of treating HIV in the West, where the disease has become a chronic condition for many, rather than a terminal illness. “And yet, not everybody benefits from those successes equally, and that’s truly true around the world,” she said.

“One of the biggest challenges is how are we going to vaccinate those who are most immunosuppressed, and [how are] we going to get HIV care to those who are most immunosuppressed to make sure that we can elevate all care,” she said.

COVID-19 vaccination is a prime example. Fifty-three percent of the global population has received the primary series of a COVID-19 vaccine, but only 8% of them live in Africa.

Although Dr. Abrams said she saw Dr. Walensky’s point about ensuring vaccination around the world, but “we have not been quite as successful as we might have hoped with vaccinating the U.S. population. And you know, I for one as a pediatrician was so excited to see the vaccine approved for children in adolescence. And yet, the uptake has been incredibly disappointing. The same with boosters for older adults.

“So I’m, wondering whether you have thoughts about how to improve vaccination in the U.S., but also how we can move forward elsewhere around vaccination?” asked Dr. Abrams of Columbia University, New YorkCity.

“I share your disappointment, especially for our younger groups,” Dr. Walensky said, adding that about 55% of U.S. teens between the ages of 12 and 17 years, about 23% of younger children between the ages of 5 and 11 have been vaccinated against COVID-19 in the United States, and about 45% of the population has received a booster.

“It’s interesting to watch. First of all, there’s never been more divisive a time, I think, in public health,” she said, which is having a direct influence not only on COVID-19 vaccination uptick but also other vaccines, such as influenza.

She said she is frequently asked by physicians: “How do you convince somebody to get vaccinated? And the truth is, I think you listened before you talk. And the problem is that takes a long time,” she admitted, adding that public health has a lot of hard work ahead.

“So, we just have to keep doing it,” Dr. Abrams said.

“Have all of us doing it,” Dr. Walensky answered, and “you know, it may not be the first conversation. It may not be the second conversation. It may be the third and fourth. So, it’s going to be time. It’s going to be listening. It’s going to be a trusted messenger” who will convince more people to be vaccinated.

Dr. Walensky took the interview as an opportunity to assure people that the vaccine is safe and effective, and that vaccine safety and adverse event reports are being monitored and investigated.

In addition to vaccination, surveillance has been an important aspect of fighting COVID-19, Dr. Walensky said, including wastewater surveillance. The CDC launched the National Wastewater Surveillance System in September 2020, and launched 400 sites in early February so that people can see trends in disease, such as the early signals of variants. This type of surveillance will be useful to detect and monitor other diseases.

“We are going to double that in the next four weeks. So, really scaling up our wastewater surveillance,” she said.

Genomic surveillance also has been scaled up. “Our genomic surveillance allows us to detect a variant with 99% confidence,” even if it appears in fewer than 0.1% of sequenced samples.

Surveillance is also being done at the busiest international airports to catch variants that might be coming into the country.

Dr. Abrams asked whether these surveillance and safety monitoring programs will remain after the pandemic, and Dr. Walensky said they are working to rebuild the infrastructure.

“I think that’s really important to recognize that we had a pretty frail public health infrastructure in 2020 when this all started,” she said. “And that was, even in light of the fact that we had had Ebola, and we had had Zika, and we had at H1N1 [influenza] in the last decade, and still there had not been a longitudinal disease, agnostic investment in public health,” Dr. Walensky said.

Over the last decade, an estimated 60,000 to 80,000 public health jobs were lost. “So, this year we were fortunate to receive an investment of $7.4 billion in the American Rescue Plan to recruit and hire public health workers, to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic,” she said, “but importantly, to also prepare us for future public health challenges to take all of that surveillance that I just talked about and to scale it up.”

And the challenge for future public health workers will be the ability to pivot quickly in response to a crisis, for instance, someone who does contract tracing for sexually transmitted diseases would be able to pivot and help with contact tracing for another disease. “It can’t be that the funding mechanisms don’t allow them to do that pivot,” Dr. Walensky said, adding that public health needs to be “agnostic.”

Another important aspect of the “new public health” is communication. Silos have to be brought down, and people have to be able to talk with each other to link data. “We’ve spent an enormous amount of time thinking about … how we can link our immunization data with our hospital data, with our testing data. And that’s been a huge challenge this year, but then how are we going to do that for other diseases? How are we going to do that for other respiratory diseases, for other diarrheal diseases?”

Both doctors lamented that there won’t be enough people interested in public health to ensure that the infrastructure is not only built but remains healthy, and attracting the next generation into infectious diseases and public health is paramount.

“We need you now because you are the people who are going to deliver … the public health of the future, the medicine of the future, the research of the future, that all of these resources we are going to invest in.

“They’re going to invest in people like you who will deliver it,” Dr. Walensky said.

But What About HIV?

“The CDC is clearly facing many other pressing priority issues. And I think here at this meeting, we’re particularly concerned about ending AIDS in the U.S.,” Dr. Abrams said, pointing to “troubling trends,” such as a resurgence of sexually transmitted infections and increased drug use. “I’m wondering if you’re concerned as many of us are that we’ve lost focus on ending AIDS in this country. And what might the CDC be doing, you know, beyond the COVID cloud to be keeping an eye on the ball?”

Dr. Walensky said some ground has been lost, but the CDC is still committed to ending HIV. “We’ve lost ground in so many other areas that we need to sort of make sure that we are not just looking under the COVID-19 lamp post but we’re looking at broader public health, and HIV is clearly one of them,” Dr. Walensky responded, adding that $117 million in the budget is being “devoted to not only rebuilding but expanding all of the work that is being done, and more than can be done in HIV.”

Actions learned during COVID-19 will be useful in the fight against HIV, she added, such as increasing the ability to self-test for HIV. “We recognize we can empower people to do their own testing,” which would enable HIV-positive people to access care more quickly.

“I think that we need to build and expand as we do, exactly as you say, and that is make sure that all that we have learned and gained in HIV continues. That momentum has to continue and ideally taking some of those lessons that we’ve learned from COVID-19, be it self-testing or PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis], navigation or whatnot, and apply them and reinvigorate them moving forward,” Dr. Walensky said.